Nerve Blocks with a Risk of Diaphragm Impact

November 20, 2024

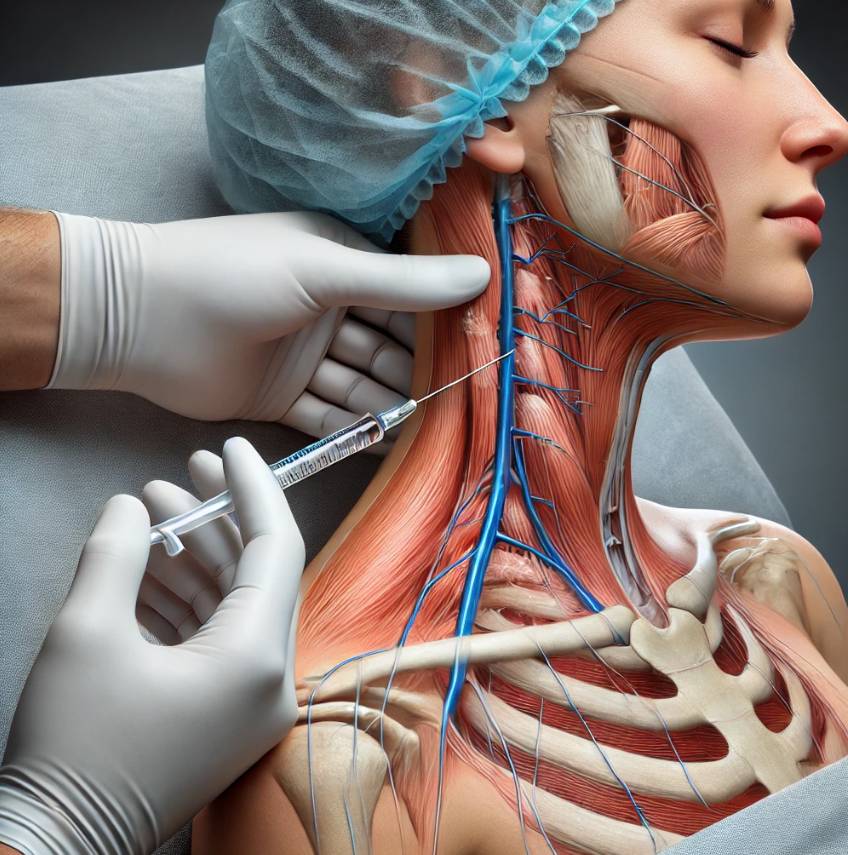

Nerve blocks are a widely used technique in regional anesthesia, particularly for surgical procedures involving the upper and lower extremities. Despite their efficacy in providing targeted pain relief and reducing the need for systemic analgesia, nerve blocks carry potential risks, particularly with regard to the phrenic nerve and its effect on diaphragm function and breathing. Although nerve blocks targeting the lower limbs do not risk impacting breathing, nerve blocks in certain areas closer to the chest require a cautious approach to avoid impacting the diaphragm. Interscalene brachial plexus blocks (ISB), commonly used for shoulder surgeries, may unintentionally involve the phrenic nerve, resulting in hemi-diaphragmatic paralysis. Because the phrenic nerve runs close to the brachial plexus, it can be inadvertently blocked, impairing diaphragm function on the ipsilateral side (1). While most cases result in transient paralysis, there is a risk of prolonged or even permanent impairment, and even transient impairment requires swift action to secure the airway.

Phrenic nerve blockade and resulting diaphragm paralysis is of particular concern in patients with pre-existing pulmonary disease. In such cases, even a partial loss of diaphragm function can lead to respiratory compromise. The proximity of the phrenic nerve to the site of nerve block administration in interscalene approaches makes the incidence of phrenic nerve involvement high, with studies reporting incidences of diaphragmatic paralysis as high as 100% with traditional ISB (2). Although the effects are generally self-limiting and resolve within hours to days, certain factors such as continuous catheter use or repeated boluses may prolong the duration of diaphragm dysfunction (3).

Recent advances in regional anesthesia have focused on the development of diaphragm-sparing nerve block techniques, such as selective nerve blocks that target specific branches of the brachial plexus while avoiding the phrenic nerve. These approaches, including supraclavicular and infraclavicular blocks, provide effective analgesia for shoulder surgery with less risk of compromising diaphragm function (3). Such techniques are particularly promising for high-risk populations, such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or other respiratory comorbidities, where even temporary diaphragm dysfunction could pose significant health risks.

In addition, certain studies have highlighted the potential role of patient-specific factors, such as body habitus and anatomical variations, in the risk of diaphragm impact following nerve blocks. For example, in patients with obesity, the increased distance between the skin and nerve structures may require deeper needle insertion, potentially increasing the likelihood of phrenic nerve involvement (4). Approaches to anesthesia should be personalized and take into account individual patient anatomy and risk factors to minimize adverse outcomes.

Although diaphragm-sparing techniques are not without their own challenges, including the need for advanced technical skill and the potential for incomplete analgesia, they represent an important advancement in regional anesthesia. As the understanding of nerve block risks continues to evolve, ongoing research into alternative techniques and nerve block strategies aims to minimize the risk of unintended phrenic nerve involvement while maintaining effective

postoperative pain control. The development of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia has also been instrumental in reducing the risk of phrenic nerve involvement by allowing real-time visualization of nerve structures and precise needle placement. Ultrasound guidance, combined with diaphragm-sparing approaches, offers an improved safety profile for patients undergoing surgeries requiring brachial plexus nerve blocks.

References

1. Cubillos J, Girón-Arango L, Muñoz-Leyva F. Diaphragm-sparing brachial plexus blocks: a focused review of current evidence and their role during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2020;33(5):685-691. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000911

2. Tran DQ, Layera S, Bravo D, Cristi-Sanchéz I, Bermudéz L, Aliste J. Diaphragm-sparing nerve blocks for shoulder surgery, revisited. Reg Anesth Pain Med. Published online September 20, 2019. doi:10.1136/rapm-2019-100908

3. Cuvillon P, Le Sache F, Demattei C, et al. Continuous interscalene brachial plexus nerve block prolongs unilateral diaphragmatic dysfunction. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2016;35(6):383-390. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2016.01.009

4. Kaufman MR, Elkwood AI, Rose MI, et al. Surgical treatment of permanent diaphragm paralysis after interscalene nerve block for shoulder surgery. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(2):484-487. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829c2f22